Helping Employees through Change

Changing employee behaviour is difficult. In fact, changing our own behaviour is hard enough: it’s not easy to establish new habits such as taking more exercise, getting more sleep and eating less. Similarly, it’s difficult to change our organisation’s make-up, shift company culture, establish a collaborative culture and change the way leaders communicate.

As a profession, communicators know that these things don’t come easily, but what’s new is that the field of neuroscience is beginning to explain why these activities are often pain points and more interestingly, what we can do about it. The idea of using neuroscience in change management and leadership communication has to be one of the most exciting developments in the workplace.

At last, we can demonstrate that communicating with employees, involving them, building strong working relationships are not just “nice to do”, “the right thing to do” or “soft”, but are essential in enabling the brain to focus and in equipping people to think and perform at their best.

Our brains find change hard

To understand why our brains find change difficult to process we need to look to prehistoric times when mankind was at its earliest point of evolution.

Fundamentally, our brains still boast the same physical makeup as our ancestors, although we do have a larger and more developed prefrontal cortex (PFC) – the part of the brain that allows us to reflect and consider.

Back then, the brain had one key driver: survival. To do this it worked on the simple principle of avoiding threats and seeking out rewards. Of the two, avoiding threats, such as the sabre-toothed tiger, was far more important to survival and so our brains developed five times more neural networks to look for danger than they have for reward.

As a result, our brains today are still subconsciously looking out for threats, five times a second.

Why is all this relevant to today’s organisations? It matters because when it comes to uncertainty, for example during a takeover, this represents a major threat. Our brains are not wired to handle this scenario calmly or objectively, so imagine an employee’s state of mind during a merger or acquisition.

The negative spiral change creates

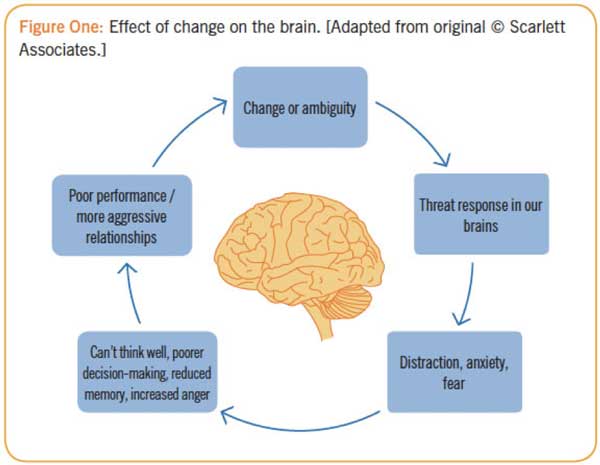

Like our bodies, our brains have a limited amount of resources and energy so when the brain is presented with ambiguity or significant change, it goes into a threat response and reroutes energy to fight or flight.

This means there is less resource available for our PFC so we become distracted, trying to work out what the threat or uncertainty means for us. This response, when we become anxious and fearful, changes the way employees see the world.

They start to see minor threats as larger than they really are, and start to see threats in the workplace where they don’t exist. For example, we all know that feeling: “Why didn’t my boss say ‘Hello’ to me this morning? He normally does…” or “What’s going on in that meeting room? Why wasn’t I asked to participate?” Colleagues are viewed as threats.

To add to that problem, the feeling of threat is contagious: if colleagues around us, or our leaders, are feeling worried and fearful, the feeling will spread. Employees are less able to focus on their work and their memory is negatively affected. Additionally, they become less perceptive as their field of focus narrows and they move to a more emotional state, unable to calm their feelings.

In fact the brain, when facing change and uncertainty, becomes like the brain of an adolescent, quick to get emotional and angry, struggling to think clearly [see Figure One].

It becomes worse still: as ability to think clearly and perform effectively is reduced, stress levels rise and this sends the sufferer further downward into a negative spiral, and performance declines even more. At the very moment when organisations need their people to be focusing and thinking clearly, the impact of change and uncertainty on the brain is having an entirely opposite effect.

What neuroscience can teach us about performing at our best

This begs the question, what can we do about this? How can we help organisations, employees and ourselves remain resilient during change? Neuroscientists have identified certain “domains” that have a major impact on our brains and therefore on our motivation and engagement.

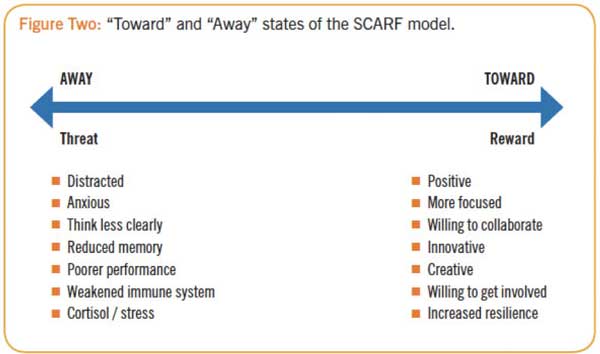

These domains can activate our brains positively or negatively, depending on whether we feel secure or threatened.

If the former, we are more focused, creative and willing to collaborate and we are also more able to learn (the “toward state”); but if our brains detect a threat, we experience all the negative emotions and behaviours that go with that state and people become difficult to influence positively [see Figure Two].

Dr David Rock summarised these domains in the SCARF model:

Status

Status is partly about where an employee sits within an organisation’s hierarchy but it’s also the extent to which they feel respected and valued. Being asked for their opinions or to help on a significant project can boost sense of status.

Knowing that they are better at a skill than others, improving at a skill or being offered a development opportunity all improve sense of status and push employees into the toward state.

Certainty

As communicators we have challenged leaders over the years to be more transparent and to share information with employees. Neuroscience now backs us up – the brain craves certainty. When it doesn’t have it, it gets distracted as it tries to work out what pieces of information mean and whether they all make sense.

Employees speculate and, because there are five times more neural networks in the brain to detect threat, they become anxious and enter the threat response. To focus, their brains need open, frequent and consistent communication.

Autonomy

This is about the need to have control over our lives, or at least the perception of control. As a rule, employees aren’t keen on being micromanaged and even advice supplied with good intentions can send them into the threat response.

Neuroscience demonstrates that involving people puts them into the toward state – willing to collaborate and to help make change happen.

Relatedness

Because human beings need others to ensure our survival, through our early years our brains are wired to be social. We need to connect with other people. Every time we meet a new person, unconsciously our brains are thinking “friend or foe?” and because we have more neurons to detect threat, our tendency is to think “foe”.

Research conducted by Dr David Amodio of New York University has revealed some interesting but disturbing facts about how the brain automatically leads us all to be biased, and we are both victims and protagonists of this bias. Neuroscience backs up the good work that many communicators and change agents undertake – when employees feel they belong to a group they enter a toward state.

Time with leaders, team meetings, informal social gatherings and team-based activities are not just nice to do, they lead employees to feel that they belong to “the ‘in’ group” and put their brains into a more constructive mindset.

Providing employees with time to meet face-to-face isn’t a luxury – it helps them to build a sense of belonging and trust, and calms the mind.

Fairness

This becomes all the more important during times of change. If things are going to be different then an employee’s brain needs to know that the process will be fair.

Fairness is rooted very deeply within us – every child is very quick to point out if something is not fair.

Empathy

Other domains are also emerging as being important. Dr Naomi Eisenberger of UCLA conducted research on empathy that demonstrated how much more resilient employees will be if they feel they are in the presence of an empathetic person – they’ll try for harder and longer at new tasks.

This is an important point for leaders in particular to note.

Two questions for you

- Take a look at the domains: which one matters most to you? All domains matter to all of us but we do have different preferences and these preferences can change in different contexts.

- Over the next 24 hours, observe your colleagues, friends and family. When someone gets annoyed or goes into an “away state”, analyse why that might be. Which domain has gone into a threat state? Has their status been undermined in some way, do they feel excluded from the group?

Source: Hilary Scarlett, Scarlett Associates